There are a bunch of different reasons that serious endurance athletes generally don’t have big pipes. The most obvious one is that they spend a lot of time running and pedaling and so on, and very little time pumping iron. There may also be an “interference effect,” in which endurance training directly counteracts some of the effects of strength training. And it may be that marathoners simply aren’t wired to get big: researchers have long suspected that slow-twitch muscle fibers, which are most plentiful in endurance athletes, don’t respond to training in the same way as fast-twitch fibers.

This last idea is of particular interest to people like me, who after long years of endurance training have grudgingly accepted that their long-term health would likely benefit from packing on some more muscle. I’ve included strength training in my routine pretty consistently over the past decade, but I’m in no danger of needing to buy bigger T-shirts. So I’m interested to know whether my muscular profile is ill-equipped to add mass, and if so, whether there are any particular training strategies that would work best for me.

A new study in the Journal of Physiology, led by Kim Van Vossel and Wim Derave of Ghent University in Belgium, takes aim at both of these questions. A little over a decade ago, Derave and his colleagues developed a new method of non-invasively estimating the proportion of slow- and fast-twitch fibers in a given muscle—a big improvement over the traditional (and painful) method of taking a muscle biopsy. Since then, Derave and others have published a series of interesting studies on how fiber type affects training response, including one that I wrote about in 2020 which showed that runners with more fast-twitch fibers recover more slowly and are consequently more likely to show signs of overtraining when they increase their mileage.

Is the same true of strength training? To find out, Van Vossel and her colleagues had a group of 11 slow-twitch volunteers and 10 fast-twitch volunteers perform a ten-week strength training program. Their workouts consisted of three to four sets of four different exercises, targeting the quadriceps, hamstrings, biceps, and triceps. Each set was performed to failure at a weight of 60 percent of one-rep max. And here’s the clever part: they trained one arm and one leg on Monday, Wednesdays, and Fridays, and the other arm and leg on Mondays and Fridays only.

There are lots of ways to analyze the data, but headline finding is straightforward—and surprising. Muscle fiber type didn’t have any impact on how much muscle size (as measured with a full-body MRI) or strength increased. The subjects did get bigger muscles, with overall gains ranging from 3 to 14 percent. And they got stronger, with increases ranging from 17 to 47 percent. But fiber type didn’t matter.

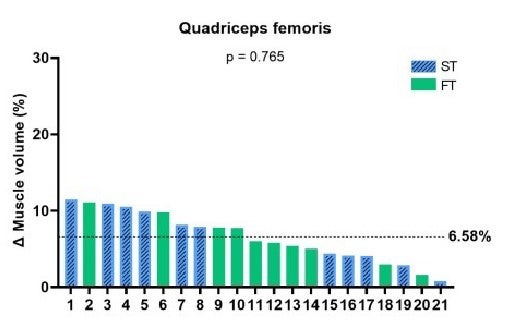

Here’s an example showing the gain in quadriceps volume for each subject, which ranged from basically nothing to just over 10 percent. The blue bars show slow-twitch subjects, and the green bars show fast-twitch subjects. There’s no discernible pattern.

There was also no interaction between fiber type and training frequency. Van Vossel and her colleagues had hypothesized that the fast-twitch people might do better with twice-a-week training, since they recover more slowly. But that didn’t turn out to be the case.

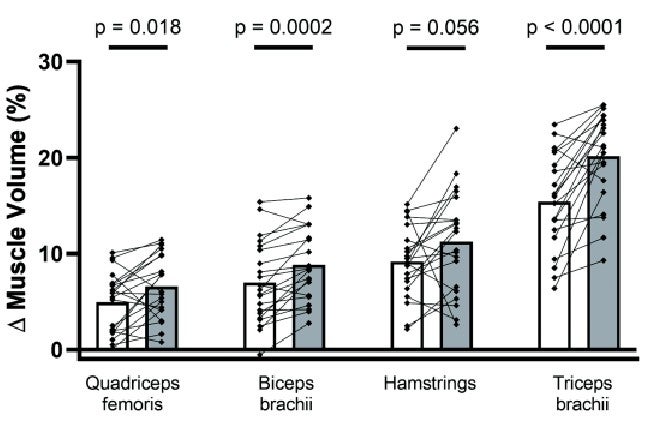

However, training frequency did matter. Both fiber types saw bigger gains in the limbs they trained three times a week compared to the ones they trained twice a week. Here’s the increase in muscle volume for the four different muscles, with twice-a-week limbs shown by white bars and three-times-a-week limbs shown with grey bars:

This may seem obvious: training more generally produces better results. That doesn’t always pan out, though. Some studies have found that three hard workouts is too much, particularly in older adults. Others have found that you can get significant gains even with just one workout a week. The optimal training frequency probably depends on who’s exercising and what exercises they’re doing, but in this particular case—novice strength trainers doing a fairly simple program—three times a week was better for muscle size. It didn’t have a significant effect on strength, though.

There’s one other important point, which is that the slow-twitch subjects had to accumulate more reps to achieve the same gains. Recall that each set was performed to exhaustion at 60 percent of one-rep max. Fast-twitch muscles are more fatiguable, so fast-twitch subjects tend to reach exhaustion sooner at a given relative intensity. In fact, a 2021 study suggested using the number of reps you can complete at 80 percent of one-rep max as a marker of whether you’re predominantly fast-twitch (8 reps or less) or slow-twitch (11 reps or more).

In Van Vossel’s study, the slow-twitch subjects were able to complete more reps at 60 percent of one-rep max, which meant they lifted a grand total of 25 percent more weight, on average, over the course of the ten-week training period. That suggests that if the training program had instead been assigned as a certain number of reps at a given relative intensity, the fast-twitch subjects would have gained more muscle. But if you train to a given level of fatigue (failure, in this case), then everyone gains the same amount of muscle—on average, that is.

On an individual level, as I can attest, everyone definitely doesn’t gain the same amount of muscle from the same training. There’s huge variation in outcomes, in this study and every other study like it. But this variability can’t be explained by muscle fiber types. Unraveling that riddle will have to wait for future research. In the meantime, the study offers some useful insights. Slow-twitchers probably need to do more reps than fast-twitchers to get a comparable stimulus. Three workouts a week trumps two for muscle size. And you can’t blame your muscle fibers for your failure to bulk up.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.